During the pandemic, I at times was desperate for boxing content during the waits between live cards, and to scratch that itch, I turned to various YouTube rabbit holes, but I also dove into books about “The Sweet Science,” including classics from authors such as Liebling, Hemingway, and London. And that jump into literary boxing history got me thinking about just how far back the fistic tradition goes. Well, turns out it goes as far back as two of the very oldest pieces of Western literature we have: The Iliad and The Aeneid. And believe it or not, the depictions of boxing action are as dramatic as anything we might read today, complete with trash talk, merciful stoppages, and one-punch knockouts.

Homer composed The Iliad around 800 BCE, and even then boxing had been formalized. One of the “heavy events,” since it was dominated by large athletes, along with wrestling and the brutal combat sport known as pankration, boxing had an important place in Greek society almost three millennia ago. Homer shows us a boxing match which was part of the funeral games to honor a fallen warrior, Achilles’ best friend, Patroclus. Though boxing would not become an Olympic sport until 688 BCE, its importance to the Greeks is clear from Homer’s account.

The match begins with what we would now refer to as “the purse,” or the prize. There are no bids or negotiations, but before we even know the combatants, we are told what the two boxers will be fighting for. Achilles himself sets the terms, declaring the victor will win a six-year-old mule before brandishing a two-handed goblet as the consolation prize for the loser. He then invites two men to come forward and do battle.

Immediately, the trash-talk and intimidation begins. Epeios, a “huge and powerful” soldier, rises to his feet and says, “Let the man come up who will carry off the two-handled goblet,” demonstrating the same emulsification of arrogance boxers exude today. He continues, “Let those who care for him wait nearby in a huddle about him to carry him out, after my fists have beaten him under.” Not so different from the trash talk we hear in the modern sport, such as Muhammad Ali declaring, “If you even dream of beating me, you’d better wake up and apologize.”

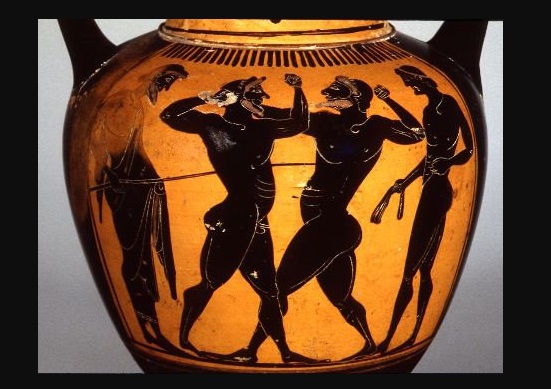

Only one man answers the taunts of Epeios, Euryalos. He is “a godlike man,” who says nothing in the text, though Homer makes mention of his fighting pedigree, noting that Euryalos’s father had gone to Thebes and “there in boxing defeated all the Kadmeians.” The combatants ready themselves by putting on the ancient version of hand wraps, leather strips called meilichae. These are different from what is perhaps the most famous image of ancient boxing hand protection, the oxys, a much thicker leather seen on the famous statue “The Pugilist at Rest.”

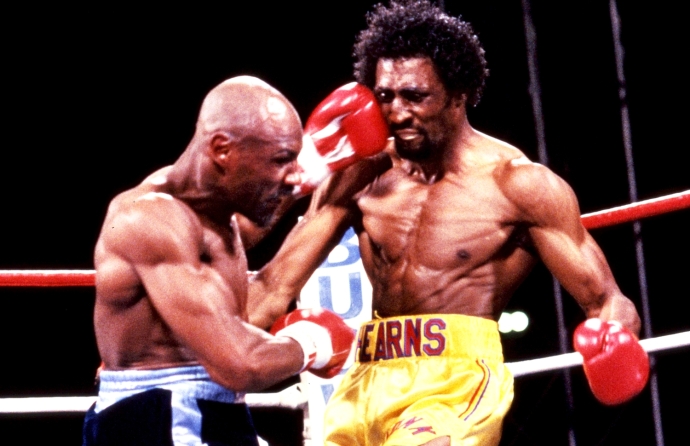

The fight itself isn’t terribly long, only fourteen lines. Zone out for a moment when you’re reading and you’ll miss it, a little like running to your kitchen for a beer before the opening bell and only seeing replays of a first round knockout. Even in this short account, though, we see the strategy of ancient boxing. When they start, “their heavy arms were crossing each other,” eliciting images to modern readers of brawls like Dempsey vs Firpo or Hagler vs Hearns, when the fighters don’t bother with any warming up or “feeling-out” interval and instead get right to the carnage. But the knockout happens when Epeios “came in, and hit [Euryalos] as he peered out from his guard,” showing that timing and accuracy have always been most important skills for a boxer.

Sportsmanship and respect were also part of the sport in Homer’s day, because even though he lived up to his trash talking, Epeios does not gloat over Euryalos. Instead he helps to lift his foe to his feet before his companions “led him out of the circle, feet dragging as he spat up the thick blood and rolled his head over on one side.”

Roughly eight hundred years after Homer’s account, the Roman poet Virgil wrote The Aeneid. Virgil was an open admirer of Homer, and based much of his work on his predecessor’s famous poem, right down to individual scenes, including a boxing match. And just as in The Iliad, the boxing match takes place at one of several funeral games, this time in honor of the anniversary of Aeneas’ father’s death. It also involves similar prizes: a bullock for the winner, a sword and helmet for the loser. Virgil’s entire scene is in fact an echo of Homer’s, but it is more filled out, taking up 160 lines, the additional material showing that ancient boxing shared many of the core traits of today’s sport.

The scene begins with a man named Dares answering Aeneas’ call for fighters. Like Epeios, he must wait for a challenger and proceeds to trash talk: “Goddess-born, if no one dares to face me then how long am I to stand? How long to linger?” Finally Entellus does answer Dares’ call, and we find out that Entellus is a former champion boxer who feels too old to compete anymore.

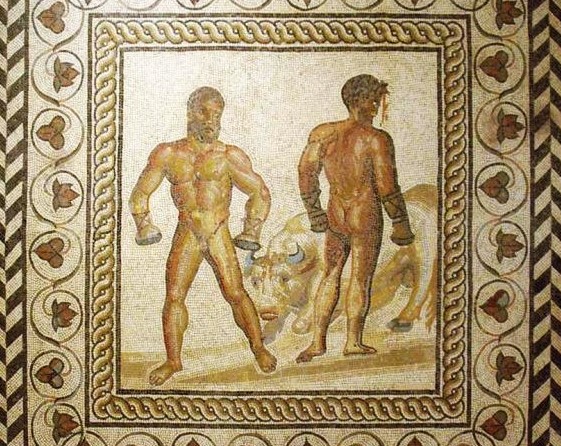

But when Entellus throws his gloves into the ring, the crowd is stunned by the sight of them, “so mighty were the oxen whose seven mighty skins were stiff with lead and iron sewn inside,” the gloves bearing the stains of “blood and spattered brains” from previous fights. Before Entellus, these same mitts had belonged to Eryx, a legendary boxer who was only defeated by Hercules. Even the brash Dares is startled by this, so Entellus offers to use different gauntlets, and each contestant receives fairly matched weapons. The scene is reminiscent of today’s fighters agreeing on the weight of their gloves and making sure officials observe their opponents wrapping their hands, knowing that even a small discrepancy can have a major effect on the bout.

One notable difference in this scene, between both Homeric and contemporary boxing, is that the gloves are weapons and not protection. The lead and iron sewn into them makes them cestus, not the meilichae from Homer. The weapon-like cestus is more commonly associated with Roman gladiatorial bouts, and so it makes sense that this would be what Virgil has his pugilists using.

Once the bout starts, it’s a classic match-up of an older vs a younger fighter: “The Trojan [Dares] is better in his footwork, relying on his youth; the other is strong in bulk and body, but his knees are slack and totter, trembling…” Here it’s important to remember that the ancients did not have weight classes, so a smaller man could always face a much bigger one, putting agility up against power. At first it seems like the younger, faster, more conditioned man will win, as after they throw some exploratory punches the larger man goes for broke with a crushing blow, but Dares slips it and “Entellus spent his strength upon the wind.” To add further embarrassment, Entellus falls over from his momentum, “just as at times a hollow pine, torn up from its roots on Erymanthus or on the slopes of giant Ida, falls.”

Here it seems like Dares is in full control but, as with the best boxing drama, everything flips in a moment. Entellus is so embarrassed from his mishap that he is seized with fury and he proceeds to beat Dares all over the field, doubling up blows with each hand—even two thousand years ago a sign that a fighter was in total control of his opponent. The pounding is so brutal that Aeneas “snatch[es] away exhausted Dares,” stopping the fight in the manner of today’s referees throwing their arms around a combatant no longer able to protect themselves.

Entellus takes his victory in a strange way. After Dares is carried off, Entellus, cestus still on his hands, smashes in the skull of the ox, killing it, and says, “Oh Eryx, unto you I offer up this better life instead of Dares’ death; here—victor—I lay down my gloves, my art.” After just coming out of retirement, Entellus retires from the sport again, which somewhat cynically resembles the way contemporary boxers retire multiple times over. The destruction of the prize, though, shows us that Entellus only put on the gloves in the first place for pride, for sport, and for “art,” traits that today’s fans wish they saw more often in 21st century boxing.

It won’t take a curious boxing fan long to read these millennia-old accounts of pugilism. They are enjoyable and beautiful in themselves, but also give a perspective on just how far back go the core tenets of boxing. Given this history, it’s probably not an accident that boxing was one of the first sports to resume after the pandemic stopped everything. It makes sense: as Homer and Virgil show us, boxing is a fundamental feature of our sporting culture. — Joshua Isard