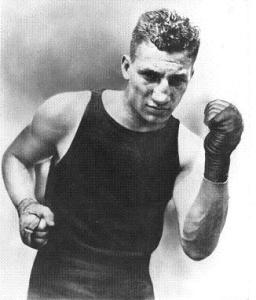

There is no disputing the oft-repeated truth that Benny Leonard will forever stand as one of the finest boxers who has ever lived. Not as well known is the fact that fellow Jewish pugilist Lew Tendler also deserves high ranking, not only as one of boxing’s greatest southpaws, but also as one of the best to never win a world title. Leonard and Tendler competed in what some consider the strongest lightweight division in boxing history with Johnny Dundee, Rocky Kansas, Willie Ritchie, Freddie Welsh, Charley White, Johnny Kilbane and Ritchie Mitchell among the cast of excellent contenders and champions. Leonard bested them all — in the process, establishing himself as the greatest lightweight of all-time — but no one came closer to defeating a prime Leonard than Tendler did in their first meeting, held in front of a mob of sixty thousand in Jersey City, New Jersey.

The official verdict, after twelve hard-fought rounds, was a “No Decision,” a common result at this time. It must be remembered that boxing was illegal in various jurisdictions and, even where it was permitted, it was commonly viewed as a most undesirable form of competition as it attracted the reprehensible activity of gambling. Many states banned official decisions, the logic being this would both discourage betting on fights and eliminate the possibility of judges being bribed. As a result, if a match went the distance, no winner was announced and it fell to the newspapers to report on the contest the next day and declare a victor.

Hence, “newspaper decision” entered the lexicon, forming a major component of Benny Leonard’s career. More than half of his 219 matches were “no decision” contests and the ridiculous rule actually delayed the great Leonard’s acquisition of the world title. In 1916 he fought lightweight champion Freddie Welsh, but the gold belt could only change hands if Leonard scored a knockout. The match went the scheduled distance, and while the next day the newspapers unanimously declared “The Ghetto Wizard” the victor, Welsh kept his crown. The following year Leonard challenged Welsh again but this time succeeded in forcing a stoppage, battering the champion with right hands and knocking him down three times in round nine before the referee finally called a halt. The huge Jewish community in New York City exulted as one, the fans literally carrying Benny on their shoulders after his win.

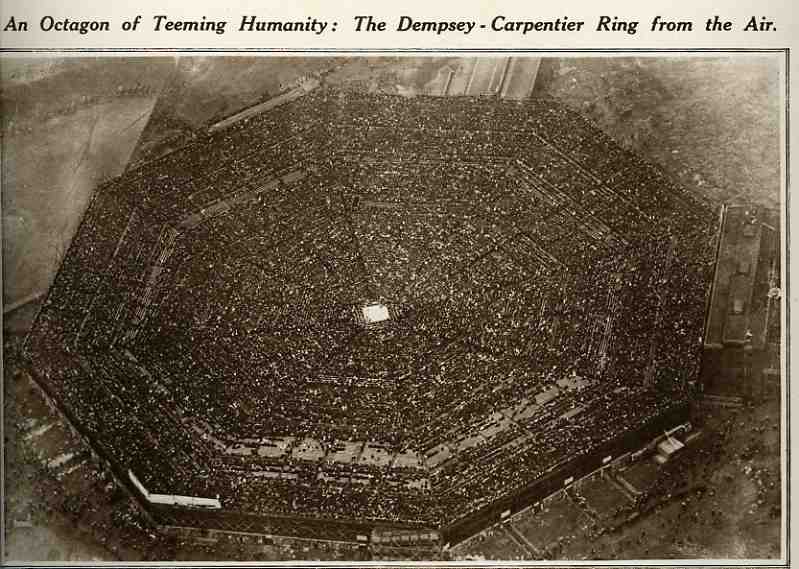

The simple fact was, if the “no decision” rule discouraged gambling (a dubious conceit in itself), it did nothing to reduce boxing’s immense popularity, with the biggest matches yielding huge paydays for both organizers and participants. The previous July, Jack Dempsey had defended his world heavyweight crown against light-heavyweight champion Georges Carpentier, the clash producing the first million dollar gate in history and attracting over eighty thousand to a specially built stadium in New Jersey called Boyle’s Thirty Acres. A lengthy list of public figures attended, including William Vanderbilt, Henry Ford, Al Jolson, Ralph Pulitzer and John D. Rockefeller.

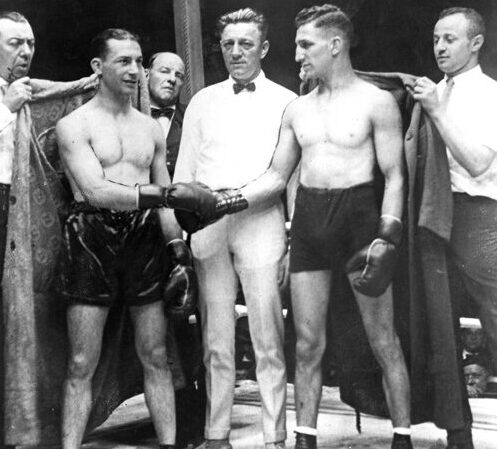

The man behind the Dempsey vs Carpentier “Battle of the Century,” Tex Rickard, knew a winning formula when he saw one, and decided the following July people would again be in the mood for another big outdoor boxing event on the holiday weekend. This time he looked to the smaller men for a compelling match-up and found it in the lightweight division. It was the classic confrontation, matador vs bull, with Leonard the stylist and consummate boxer sporting a lightning right hand, and Tendler the rugged southpaw brawler with the powerful left.

While not as massive an event as Dempsey vs Carpentier, Leonard vs Tendler I was easily the biggest fight of 1922, this the consequence of the significant rivalry that had developed between Benny and Lew in the newspapers. In fact, Tendler had been dogging Leonard for well over a year, demanding a chance at the title. They had been slated to meet in Lew’s home city of Philadelphia the previous summer, but Leonard injured his thumb in training and the bout was first postponed and then cancelled.

Tendler didn’t buy it. Everyone knew Leonard had enormous difficulty making the lightweight limit of 135 pounds and preferred competing in non-title, over-the-weight bouts. Tendler was so convinced that Leonard had walked away from the fight because of the scales that he insisted his manager collect a five thousand dollar forfeit which Benny had posted to guarantee the match. Now Leonard was as irritated with the impatient Tendler as the challenger was vexed with the more popular champion. The two traded barbs in the newspapers and the press gleefully played up the bad blood, stoking the public’s eagerness for the showdown.

And it was clear from the opening bell that Leonard had a very serious challenge on his hands that warm July night. An aggressive Tendler struck with hard right hands in the opening round, one of them opening a gash above the champion’s left eye. At every opportunity Tendler bore in, looking to pummel Leonard’s ribs and slow him down. They wrestled and mauled in round two, Lew landing borderline low blows, and in the third he continued to go downstairs, receiving a sharp warning from the referee when some of his punches strayed below the belt.

The action intensified in the fourth with both men getting home their hardest punches thus far. Leonard connected with a right that momentarily staggered his foe, and seconds later Tendler buckled the champion’s knees with a left. At the bell it was the challenger again landing stinging right hands and it was clear the southpaw had swept the first four rounds.

Leonard came back to take a close fifth and in the sixth he had Tendler bleeding and in difficulty after landing a series of rights and a hard uppercut. The southpaw appeared to be tiring while Benny worked to seize control of the contest, easily out-boxing the challenger in round seven. But then came the eighth and the closest Tendler ever got to winning a world crown.

The one tactic in the battle which had surprised many, including the unflappable Leonard, was Tendler’s use of his right lead. Instead of merely jabbing with it to set up his powerful left, Tendler had turned it into an offensive weapon and Leonard had to be wary of it. In the eighth the challenger continued to be the aggressor, stalking Leonard, and about a minute into the round he threw a quick, sharp right hand as he came forward, before unleashing a wicked left cross behind it. The shot landed flush and the great Benny Leonard almost went down. His legs buckled, his body sagged, and he had to seize Tendler around the waist to regain his balance. He desperately held on, clutching at Tendler’s arms and head and pushing him backwards across the ring as the challenger tried to break loose. And then, with Leonard seemingly one punch away from defeat, the ever-crafty champion began to talk.

The newspaper accounts the next day all made note of Leonard’s volubility at this most crucial juncture in the match. According to some he appeared to be complaining angrily to Tendler about his rough-house tactics and low blows. Others would swear they heard Leonard and Tendler conversing in Yiddish. But as “The Ghetto Wizard” himself would tell it years later, he sought to conceal his vulnerability and buy himself precious time by calmly acknowledging the blow which had almost decked him.

“I said, ‘That was a good punch, Lew.’ I said it in a friendly, matter-of-fact tone of voice and it put the fight on a different plane. Lew snarled, ‘Never mind that, come on and fight.’ But I stuck out a restraining hand and said, ‘No, Lew. That was really a good punch. It was all right.’ Lew paused again, and by that time I had recovered my senses.”

Whatever the case, Leonard utilized some quick thinking and crafty stalling tactics to disrupt the challenger’s attack. In a matter of seconds Lew’s chance to inflict major punishment or stop Leonard had slipped away, and by the end of the round it was the champion scoring with sharp blows as more blood seeped from Tendler’s mouth.

The ninth was the slowest round of the fight with neither battler having a decided edge, but in the final three rounds, Leonard took control. Throwing his heavy right with greater confidence, he stunned Tendler several times during the spirited tenth and in the final two rounds out-boxed his tiring challenger with relative ease. Still, some at ringside thought Leonard’s rally in the latter stages too little and too late.

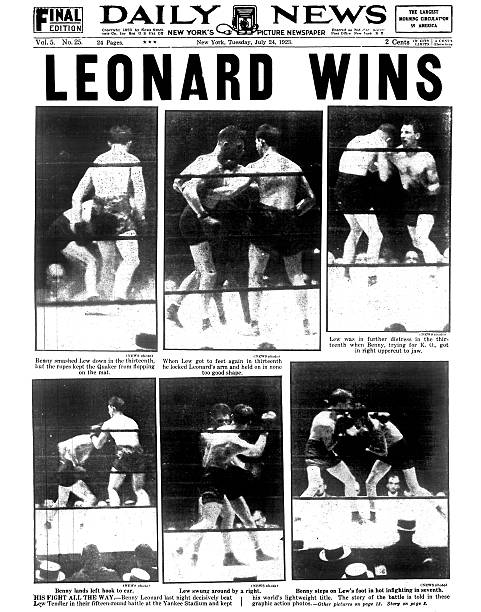

But thanks to the “No Decision,” rule Leonard kept his title in any case. The newspapers the next day offered differing opinions. Most gave it to Leonard, but by the closest of margins. A few thought Tendler had done enough to earn the nod, while more scored it a draw. Ring magazine seemed to represent the general consensus with their pronouncement of “Leonard by a shade.” It is testament to Benny Leonard’s greatness that this would be the closest he ever came to losing his world title in the ring. The following year he and Tendler met again, this time at Yankee Stadium, and this time there was no newspaper decision as “The Great Bennah” took a clear-cut and official points verdict after fifteen rounds. – Michael Carbert