In boxing history, there are the champions and there are those who fight among them. For every Muhammad Ali, Joe Louis and Jack Dempsey, there were hundreds of pugilists who aspired to that kind of greatness and renown but fell far short. Of course a fighter can’t help it if they’re toiling in the shadow of legends and playing second fiddle to the likes of Dempsey and Louis is nothing to be ashamed of. Jack Sharkey, “The Boston Gob,” was a fine fighter and a celebrity in his own right, but Dempsey and Louis were cultural juggernauts and two of the best heavyweights boxing has ever seen.

Thus Sharkey has been largely considered second best, however unfair that may be. After all, he was a fisherman who found himself lacing up a pair of boxing gloves by accident, not a desperate pug with nowhere else to go. That he got as far as he did is incredible.

“I started out as a fisherman,” Sharkey told The Ring in 1979. “When I was a kid I used to catch bass with my bare hands and sell them. Old-timers still remember me walking down the street carrying eels on my back.”

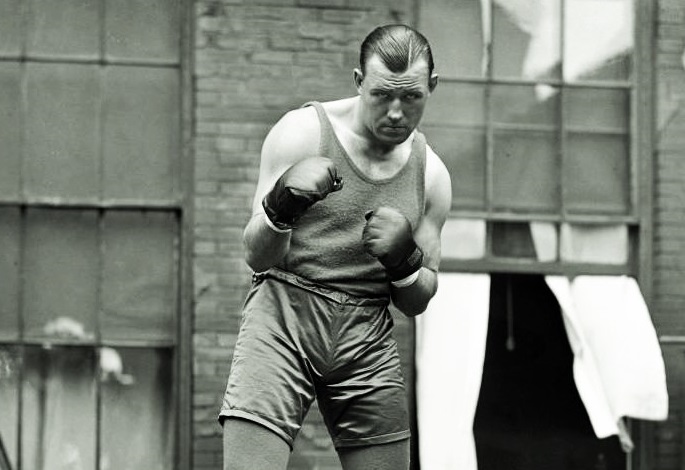

The son of Lithuanian immigrants in New York, Jack Sharkey was born Joseph Paul Zukauskas and moved to Boston as a boy, but he wasn’t much of a fighter growing up. It wasn’t until he served in the U.S. Navy that Sharkey first stepped into a boxing ring, and it was only because a midshipman told him to substitute in the next fight or he wouldn’t get shore leave. Following a few dozen fights, Sharkey was the Atlantic Fleet champion and so he eventually headed back to Boston for his first professional dust-up.

Boston sportswriter W.A. Hamilton said of Sharkey’s stint in the Navy, “[It] was not without event. He met the toughest and roughest customers in the world, and his knowledge of fighting was gained in combats where money meant nothing. The navy is a great place to develop fighters. If you start out to be a fighter in the navy you have to show something, and Sharkey was one of those who gave them some real thrills.”

But before Sharkey could make his debut, he was offered $100 to find a new name to replace his given one, deemed too ethnic by a local promoter. So Sharkey and his manager Johnny Buckley combined the names of new heavyweight champion Jack Dempsey and a tough fellow sailor who once challenged for the heavyweight title, Tom Sharkey. And the name stuck.

Sharkey sent Billy Muldoon to the canvas three times with right hands for a first round stoppage in his professional debut in January of 1924. It was later reported in the Boston Herald that Babe Ruth had attended, perhaps an early indicator of acclaim to come, but there was plenty of work to be done.

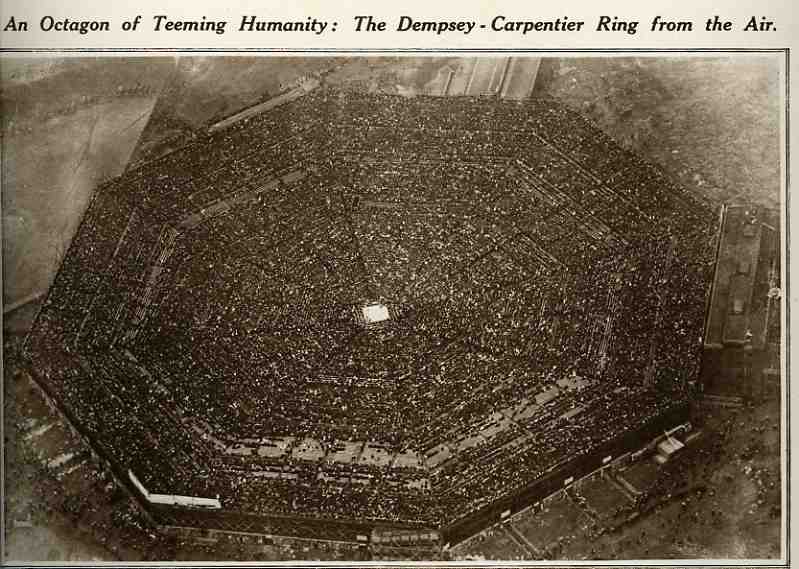

The U.S. still had Dempsey Fever. It hadn’t even been three years since the heavyweight champion thrashed Georges Carpentier on a random plot of land in New Jersey, attracting an enormous gate of $1.7 million. But Dempsey, seemingly content to party and revel in the prestige that being champion brought, made only two title defenses since defeating the Frenchman. In many ways it left the division open to develop new attractions, and Sharkey attempted to fill the gap.

In his second bout, Jack threw down with Pat “Battling” Hance, a former Army man who tried to exchange with Sharkey and was stopped in two rounds. All at once, Boston’s print media took notice of the 21-year-old prospect and Sharkey was honorably discharged from the Navy. It was the perfect time for him to become a full-time fighter, even if he was still learning on the job.

Again a sort of Army rivalry was played up as Sharkey trounced his third opponent Dan Lucas, though he accidentally punched a mirror while shadowboxing in his dressing room prior to the fight. Oddly, Sharkey would soon begin to have hand injuries and transitioned from being a puncher to a boxer-puncher. “Nobody knows the pain a fighter goes through when he has bad hands,” Sharkey would later say. “There’s no pain worse except labor pains.”

Sharkey was featured in his first main event against Montreal native Eddie Record in his next outing, and Boston media began tabbing Sharkey as a future opponent for Dempsey quite prematurely. Right on cue, Record toughed out the ten rounds and took a disputed decision, but Sharkey got his revenge a month later with a seventh round knockout of Record in a bout that was broadcast by CBS Radio.

Four fights in the summer of 1924 were a breeze for Sharkey and included a win over Floyd Johnson, a nightmarish heavyweight who had lost to former champion Jess Willard. Johnson was supposed to face Willard again for good money before losing to Sharkey on points. It was then that a rough patch of just under one year began for the prospect.

A Chilean heavyweight named Quintin Romero Rojas had made landfall on U.S. soil the previous April, just months after Argentine Luis Angel Firpo’s thrilling brawl with Dempsey for the heavyweight crown created significant interest in South American fighters. It was expected that yet another wily heavyweight from that side of the equator would give the champion another run for his money, but Rojas proved to be slightly less ferocious than advertised. Nonetheless Sharkey expressed minor concern to Boston press when matched with Rojas for late August.

As it turned out, Sharkey had reason to worry as the Chilean absorbed punch after punch and leveled Sharkey at the end of round eight with a left hook. He was saved by the bell, but according to The Boston Herald, “The referee could have counted a thousand for all that Sharkey could realize, for the local man was dead to the world and utterly without conception of his surroundings.”

When round nine began, Sharkey collapsed into a heap without a punch being landed and the fight was halted. Over the next six months, Sharkey dropped two decisions to Charley Weinert and one to Jim Maloney, with whom Jack would develop something of a cross-town rivalry over the coming years.

It was a controversial win over Montreal-based Jack Renault in April of 1925 that put Sharkey back on the path to title contention. Though Renault, a natural counter-puncher, seemed to outbox Sharkey for much of the fight, local officials nudged the decision to the “Gob.” Sharkey would then lose only once in the next two years, to Bud Gorman, and it was avenged. From May of 1925 to May of 1927, Buckley guided Sharkey to wins over Johnny Risko, George Godfrey, Harry Wills, Eddie Huffman and former light heavyweight champion Mike McTigue. But during this time Dempsey suffered a rough defeat to Gene Tunney, rattling the boxing world right to its center.

Three of Sharkey’s wins during that two-year period were against Maloney, his Boston rival. Maloney was set to fight Dempsey in a tune-up for his Tunney rematch, but again Sharkey trashed someone else’s plans. After defeating Maloney in front of a crowd of some fifty thousand in May, Sharkey declared, “I want Tunney. He’s the next man for me. But if I have to, I’m ready to battle Dempsey.”

As it turned out, the 16-1 streak indeed led him right to Dempsey’s doorstep. But any and all noise created by Sharkey’s stoppage of his old rival Maloney was immediately silenced the following day when Charles Lindbergh successfully completed his record-setting flight across the Atlantic. No other news mattered. For the time being, Dempsey was old hat, as was his more prudent successor. The boxing world still turned though, and Dempsey’s promoter Tex Rickard told press, “If Dempsey does decide to return to the ring, he will have to meet Sharkey. There are no two ways about that.”

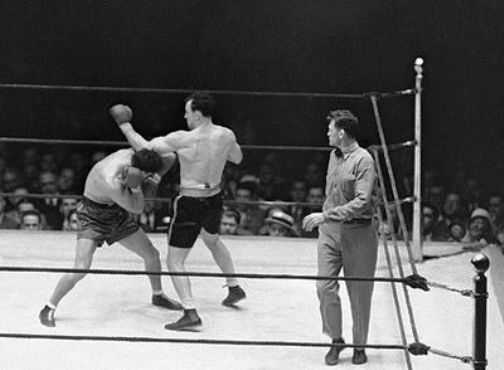

Dempsey was popular enough that the public was willing to buy a variety of excuses for Jack’s defeat to Tunney, all but the truth that Dempsey had lost some of his edge and been out-foxed by a very crafty technician. Dempsey knew better and when the Sharkey fight was signed he trained to avoid the Bostonian’s jab, which confused reporters who had only ever seen him aim to annihilate his sparring partners. It didn’t work anyway, because “The Manassa Mauler” only boxed one way and Sharkey out-fought him, rocking him several times in the first five rounds. It looked as though “The Manassa Mauler” was heading toward retirement until his punches began gravitating toward Sharkey’s midsection and lower in round six.

Famously, in round seven Dempsey clipped Sharkey low with a series of punches. When Sharkey turned to referee Jack O’Sullivan to complain, Dempsey reached Sharkey’s chin with a short left hook, his best punch, and just like that Sharkey was done for and could only shake his head when the count of ten was reached. Buckley unsuccessfully attempted to get the outcome overturned, but immediately after the fight reporters pressed Sharkey for a response to claims that he was continuously fouled. “Aw, shut up,” he told them. “It’s all in the game.”

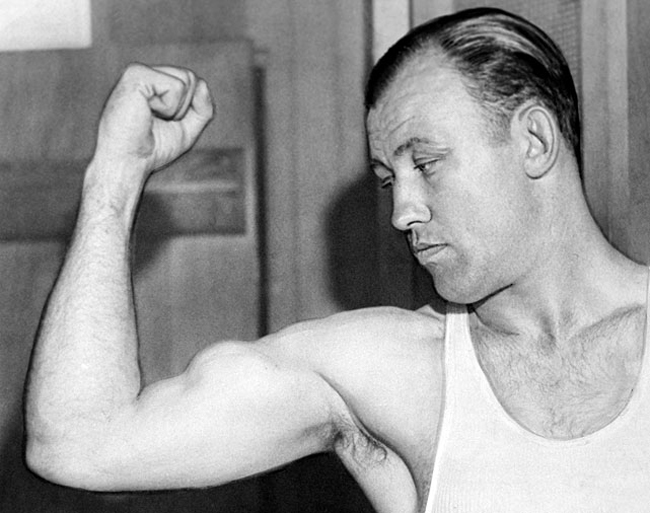

Also part of the game were the jeers and boos Sharkey often received after that for daring to oppose a giant like Dempsey, and then Sharkey picked up another nickname: “The Weeping Warrior.” It was due to his tendency to get emotional, win or lose, but later also attributed to his surly reaction to the Dempsey loss.

Six months off did Sharkey little good, as he fought to a draw with Tom Heeney and lost a decision to Johnny Risko shortly thereafter. But Sharkey chalked the losses up to bad luck and bad hands before stringing together eight wins over recognizable contenders like Young Stribling, Jack Delaney and Phil Scott, and a win over former light heavyweight champion Tommy Loughran for good measure. It was another respectable set of victories and it lined Sharkey up for an opportunity to fight German contender Max Schmeling for the title Gene Tunney had recently vacated when he retired.

Schmeling and his manager Joe Jacobs intimated before the fight that they would capitalize on Sharkey’s tendency to get discouraged in a long, drawn out affair. His hand problems likely factored in as well, as Sharkey later said, “You hit one of these guys flush on the lug and he keeps coming at you and you say to yourself, ‘How do I get out of this ring, where’s the exit, the hell with trying to knock him out, I’m just busting my hands!’”

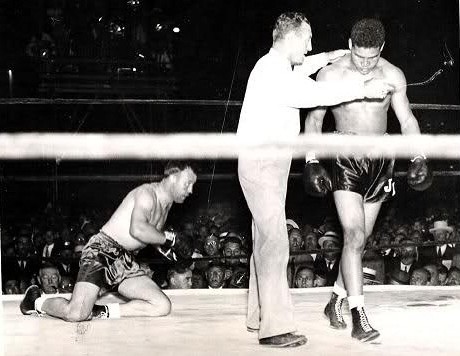

As he had before and would again, Schmeling relied on strategy more than physicality and braced himself for early punishment. Sharkey scored well moving forward, though Schmeling had some success with his left hook. In round three Sharkey rattled Schmeling with crosses and uppercuts, and somehow the German kept his composure and lashed out at the start of round four. Toward the end of the round Schmeling launched a hook that was ducked and Sharkey countered with an extremely low left uppercut that crumbled the German. Sharkey was disqualified, and Schmeling became the first to ever win the heavyweight title on a foul.

“I am not satisfied,” Schmeling told James P. Dawson of Fight Stories after the bout. “I do not want to be champion this way. Better I had knocked out Sharkey or beat him on a decision than to win by a foul. There is something missing in such a victory.”

The new champion was just as inactive as the previous two and Schmeling waited a year before defending his title against Young Stribling. Jacobs reportedly got in the way of a return bout with Sharkey who would have to wait two years for another shot, while Schmeling’s title became split as the New York State Athletic Commission stripped him of recognition in the state. In the meantime, Sharkey took on former welterweight and middleweight champion Mickey Walker expecting an easy fight and a nice payday. But “The Rumson Bulldog” instead gave Sharkey everything he could handle, overcoming a 30-pound disadvantage to draw with the ex-gob. But without looking back, Sharkey moved on to bigger prey in Italian contender Primo Carnera.

This time Sharkey was the one tangling with the bigger man as he spotted Carnera nearly 60 pounds. But the big man hit the deck in round four and was discouraged from landing with his meaty right fist as Sharkey angled away and maneuvered deftly to a 15 round decision win. It was a worthy victory, and considering Sharkey could have been guaranteed a Schmeling fight, it was a dangerous risk. But the rematch would come, even if it wouldn’t be for many months.

In June of 1932 Sharkey got his rematch with Schmeling, and at long last, the title. The New York Times called the fight “a battle that was altogether lacking in thrills … a methodical, systematic encounter of almost unvarying style.” A safer fight was what Sharkey needed, so that’s what he fought, and won. With the big victory, Sharkey, for the first time ever, took a vacation from the fight racket. When he sat out before it was because a deal couldn’t be reached for a Schmeling rematch, but this time the champion took time off and gained weight.

Primo Carnera had been busy since his loss to Sharkey, fighting 29 times and losing only twice, though many of his wins were deemed suspicious by spectators and media, and his association with mafioso Owney Madden was often blamed. As clubbing and primitive as he could be, the relative vacuum of power allowed the 6-foot-5 Carnera to become a force at heavyweight and he earned first crack at the new champion. For Sharkey, the rematch was more personal as a fighter he managed, Ernie Schaaf, died immediately after a late round knockout at the hands of Carnera in February of 1933.

Though Sharkey had success using his legs this time, after four rounds he struggled to fend off “The Ambling Alp.” In the sixth round Carnera landed a right uppercut that flattened the champion for the full count. It was deemed Carnera’s “secret punch,” and subject to much scrutiny in the months that followed; it was a punch that Carnera hadn’t used much before and Sharkey slid to the canvas in a curious way. But Associated Press writer Bill King reported that afterwards a dazed Sharkey had to be told what happened and how he’d ended up in his dressing room. In any case, there was a new champion again and the defeat marked the beginning of a sharp decline for Sharkey.

In seven more fights, Sharkey would only win twice: against journeyman Unknown Winston and young contender Phil Brubaker. Losses to Loughran, Kingfish Levinsky and Tony Shucco should have convinced Sharkey to quit, but defeating Brubaker lined Sharkey up to face future heavyweight champion Joe Louis for a nice pay day. And Sharkey needed the money; his career earnings had all but disappeared.

Fancying his chances against “The Brown Bomber,” who was coming off a huge upset defeat to Schmeling, Sharkey remarked before the fight, “I have always had the Indian sign on Negro boxers. Remember what I did to George Godfrey and Harry Wills?”

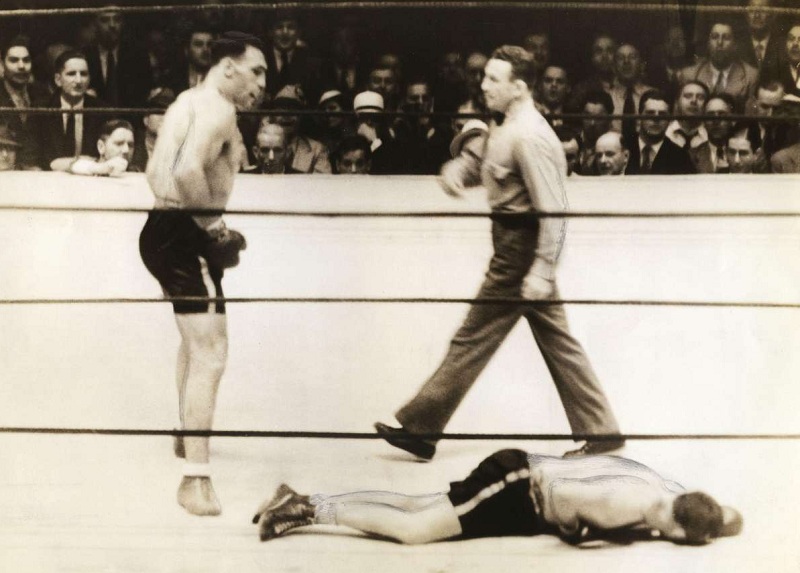

But this was 1936 and Jack Sharkey didn’t have the same legs, and Louis was a different kind of destroyer entirely. From the start of the fight, Sharkey foolishly waded into Louis’ punching range and found himself on the canvas three times before a combination put him down for the count in round three. Sharkey said to W.A. Hamilton after the fight, “Louis convinced me that I have no business in trying to continue, and now I am relegated with the others before me who tried to cheat time and nature only to be revealed in their true light.”

Thus Jack Sharkey, “The Squire of Chestnut Hill” quit the fight game and retreated to New Hampshire to revisit his beginnings. He became a fisherman once more, giving fly-casting demonstrations all over North America and basically leaving boxing behind, except for refereeing from time to time.

Sharkey’s true importance to boxing is that he bridged the gap between two classic eras for heavyweight boxing, and he helped fill the void between two great and celebrated heavyweight champions. Without any momentous or signature wins, he is unfortunately remembered as an inconsistent performer. But without a doubt Sharkey was more than just another heavyweight contender or place-holder champion. In truth he was indeed an essential player in 1920s and 30s heavyweight boxing. But ultimately a fighter is what history says he is. So “The Gob” fades to the background. — Patrick Connor