The International Boxing Hall of Fame, Canastota, New York. Photo: Alex Menendez/Getty Images

Friday, June 7: I awakened at 7 a.m., five hours after switching off the lights, and, thankfully, I felt no ill effects from last night’s bowling – at least physically. The state of my pride, however, was another story, for my scores were far below normal (110, 138 and 101, a far cry from the 165 average I carried in my final year of league bowling a decade ago). In retrospect, I suppose that was to be expected given my age (59), the fact that I’ve rarely bowled over the past year, and that I was competing on unfamiliar lanes whose oil pattern was difficult for everyone to solve. I simply lacked the sharpness or the ability to fully execute my brain’s recommendations. While I was able to hit my intended target on the lane most of the time, my balance was off, my speed was inconsistent and, by Game Three, my acuity and energy were eroded.

I suspect that on a much more violent scale and in a much more serious way physically and cognitively, fighters experience similar dullness due to chronology, ring rust and the youth of their opponents. Unfortunately, the consequences they suffer are far more dire and are often permanent. I am able to wake up with my brain cells fully intact, but the same can’t be said for the pugilistic warriors that we honor. My awareness of the damage fighters suffer has heightened with each passing year, and that has been a fairly common topic on “In This Corner: The Podcast,” which can be seen here. Host James “Smitty” Smith has been particularly emphatic about this subject, and not just because he had his own brief boxing career, but also because he has seen the effects of long, hard careers up close and personal in his role as the host of the International Boxing Hall of Fame’s Induction Weekend.

We all want to have every safety measure followed to its maximum, but it is also ultimately up to the fighter to make the final decision on how long his career should continue. Precious few ever find the perfect “sweet spot” achieved by Rocky Marciano, Lennox Lewis, Andre Ward and Carl Froch, among others, but it is our wish that this list will lengthen, because they deserve to enjoy the fruits of their hard labor with complete health and happiness.

Although I will thoroughly enjoy Day Two of this year’s induction celebration, one part of me will approach it with a heavy heart. That’s because my father passed away exactly seven years ago today, and it happened during a past IBHOF Induction Weekend. I wrote this tribute article to him in my hotel room in Erie, Pa., and for those who wonder where I get my work ethic, my attention to detail, my ability to connect with people and my drive to succeed even at a relatively advanced age, one has to look no further than my father. I have faith that the spirit and the essence that made him who he was on Earth is now smiling and is proud of what the son who bears his name has accomplished. I’m sure that our reunion in the next life will be a most joyous one, but, for now, I will continue to do my best to emulate his example.

That process, at least on this day, began a little after 9 a.m. after I sprayed on my sunscreen and packed my laptop into its bag. Today’s schedule is straightforward: Ringside Lectures from 10 a.m. to 2 p.m., the fist casting on the museum grounds at 2:30 p.m., and the Golden Boy fight card at the Turning Stone Casino starting at 6 p.m. (I plan to pick up my media credential well before that).

Writer Lee Groves with J.R. Jowett. (Photo by Eric Schmidt)

It didn’t take me long to recognize the first familiar face, and that face belonged to veteran boxing scribe J.R. Jowett, whose fight reports I read during my formative years. The induction weekend allowed me to meet and form a friendship with him as well as with Jack Obermayer, “the original Travelin’ Man,” whose fight reports were sprinkled with his tales of the road that included reviews of the diners at which he ate. His work formed the spiritual template of my travelogues, and before he passed away in June 2016, he gave me his blessing, mostly because I made sure to pay him proper respect and tribute. At 81, J.R. remains active, and he’s someone I respect.

After arriving on the grounds, I was asked to sign a Ring magazine cover by one fan and to pose for a photo by another. I still greet these episodes with surprise and gratitude because I don’t do what I do for public recognition; I do it because I love it, and that love provides the fuel with which I do my work.

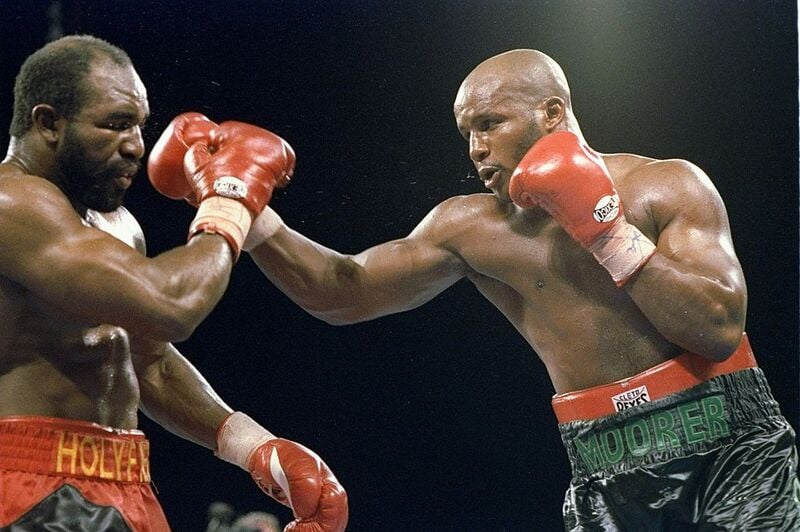

At 10:10 a.m., Smitty conducted his first Ringside Lecture of the day with 2024 IBHOF inductee Michael Moorer, who ascribed his shyness to social anxiety. He said that the impact of his being inducted hadn’t hit him yet but was sure it would do so later on. Although he is recognized as the first southpaw heavyweight champion, he said his strong hand is his right hand but that he did different things left-handed, including playing billiards.

During his reign as the inaugural WBO light heavyweight champion, there was talk of his engaging in unification fights with longtime WBA titlist Virgil Hill, tenured IBF king Prince Charles Williams and either Dennis Andries and Jeff Harding, who kept trading the WBC belt during their highly underrated trilogy. Moorer told me that while there was talk of fighting these men, it never got past the talking stage.

Eventually, the demands of making 175 proved too much for Moorer, and he said he bypassed cruiserweight to fight at heavyweight because he simply refused to ever again undergo the torture of making any weight limit. He also opined that the heavyweight division should be split into two parts, as it is with the amateurs. Yes, the WBC created a “Bridgerweight” division with a 225-pound limit (a weight class that was also recently adopted by the WBA), but while having the two weight classes make sense, I believe WBC president Mauricio Sulaiman’s unmovable position regarding the name has prevented it from gaining full recognition or respect. Simply put, beyond the back story regarding the name of a little boy, the label makes no boxing sense.

Michael Moorer (right) battles Evander Holyfield during the 1994 fight that would result in him becoming the first southpaw heavyweight champion. (Photo by Holly Stein /Allsport)

The name “heavyweight” automatically inspires a “big-time” feeling that has resulted in it remaining the most glamorous weight class that attracts the largest purses. Thus, one would think that a weight class with the “super heavyweight” label would automatically draw the same amount of money, and, as we all know, money makes the world go around, especially in boxing. If the “Bridgerweight” division is to gain the traction and the honor Sulaiman wants, he should reconsider his decision about the name while still bestowing honor on the little boy – just in a different way, such as naming an annual WBC courage award for him.

By the time Moorer’s talk ended, another familiar face placed himself to my immediate left. Bob Scudder, a native of Binghamton, N.Y., is a genuine “original” in that he was present at the first celebration. Bob’s “thunderbolt moment” as a boxing fan was Floyd Patterson’s second fight with Ingemar Johansson, and, like many, his love of the sport was furthered by watching the telecasts with his father. Now 72, Bob counts Gus Lesnevich and Vinny Paz (a.k.a. Vinny Pazienza) as his favorite fighters, and, knowing I am a member of the IBHOF’s screening committee, he asked me why neither has been inducted.

His regard for Lesnevich was ignited by an article published in World Boxing Magazine, while his passion for Paz is largely due to their shared medical experience. Like Paz, Scudder was forced to wear a halo following an automobile accident, and as proof he pointed to the scar on his right temple.

Vinny Pazienza (left) and Loreto Garza in the grinder. (Photo by Bryan Patrick/The Ring archive)

“While both of us wore the halo, Vinny’s neck was supported by a fiberglass vest, while for me it was a plaster cast,” the 72-year-old said, mentioning that the accident occurred in 1981. “I was in the plaster cast for two-and-a-half months, then a neck brace for another six weeks. The accident happened on May 10, and by Labor Day I was healed.”

All the while, the now-retired insurance salesman with Mutual of Omaha was able to work the phones at the office. In addition to the connection with the results of Paz’s accident, he strongly believes the fighter’s record merits future induction, because he feels that his ledger exceeds those who have already been enshrined. That may be true, but why allow what I believe are the errant inductions of the past to establish the permanent floor for future inductees? If that is the case, then the flood would eventually cheapen the meaning of the term “Hall of Famer.” I believe the Hall’s balloting reforms have tightened the process to the point that outrageously questionable honorees are a thing of the past, but one still can’t ignore the floor that had been previously set.

My need for sustenance prompted me to head toward the food truck and purchase a small Philly cheesesteak-style sandwich and a diet soda. The subsequent conversations at the picnic tables caused me to miss the next Ringside Lecture, which featured 2024 IBHOF inductees Jane Couch and Ana Maria Torres, and another talk that took place away from the museum grounds caused me to miss most of the trivia session that followed. I conducted last year’s session and experienced several problems that resulted in one major adjustment: Having members of this particularly knowledgeable audience take the microphone and pose their own questions, a continuation of this year’s emphasis on audience participation.

The 1:25 p.m. Ringside Lecture featured Eric “Butterbean” Esch, who retold his extraordinary transformation from wheelchair-bound to fully ambulatory thanks to Diamond Dallas Page’s DDP Yoga, which was touched upon in Part I. Reiterating his point that he would like to fight one more time to prove that anyone can accomplish anything he sets his mind to, he issued a public challenge to Jake Paul. Later in the day, it was confirmed that Paul vs. Mike Tyson, which had been scheduled for July 20 until “Iron Mike’s” recent health care, was rescheduled for November 15.

About 20 minutes into the talk, I recalled getting confirmation from Hall of Famer Julian Jackson that, as an enormous puncher, he knew he had just landed a fight-ending punch by the vibrations he felt up and down his forearm. Was it the same for Butterbean, who scored 57 KOs in 77 wins?

“When you hit someone flush, you know it immediately,” he replied.

Of fighting Larry Holmes, he said that his response to taking a flush right cross – “Is that all you got?” – prompted the then-52-year-old “Easton Assassin” to shift into reverse mode for the remainder of the match, Bean’s only 10-round fight. He said that he and Holmes are now friends, and he credited boxing as a whole for that shift in attitude.

Speaking of attitude, his present state has resulted in a bright, sunny disposition, and despite his decades-long prominence, he still gets a charge from offering encouragement to others. He illustrated this by recounting a recent story involving a 13-year-old fan. Unable to afford the price of an autograph, the kid said he’d be satisfied with a handshake. After obliging, he saw the kid crying, prompting him to approach him and ask what was the matter. The answer: “I never thought I’d ever get to meet you.”

A prime Butterbean. (Photo: The Ring)

“That made my day,” Butterbean concluded, saying that the little effort required to make someone else happy is more than worth it.

Ana Maria Torres was the first to have her fist preserved at the annual Fist Casting ceremony. During the process, John Hunt, who had overseen and executed the event until retiring last year, had hoped to make a presentation to Executive Director Ed Brophy. Unfortunately, Brophy was otherwise occupied at the Turning Stone, so Hunt decided to reveal what was inside the black bag – his own artistic portrait of Brophy. I was seated about 50 feet away, but from this vantage point, the painting bore a good likeness to its intended subject.

As Jane Couch was getting her fist preserved, the wind that made the upper-50 temperatures feel even colder finally persuaded me to leave the museum grounds and walk toward my car in the Days Inn parking lot to retrieve my IBHOF windbreaker. Before I was able to do so, Boston native Gus Reyes – a frequent inquisitor at the Ringside Lectures – spotted me and said hello. That, of course, ignited a multi-minute conversation, and in the midst of that talk the sun came out and provided us a boost of warmth. Aside from a cloudburst a couple of hours earlier, the rain had largely held off to the point where more than one person opined how lucky the area had been over the past few days.

“Everyone around us was getting hammered,” one told me.

Once the windbreaker was retrieved, I returned to my room and shared Part II on Facebook. I then drove to McDonald’s with the intent of getting some fast food, but I had the misfortune of taking my place in line at a time when eight other vehicles were ahead of me. It took nearly 20 minutes for me to finally get to the payment window, and in that time, I made sure to retrieve enough loose change to get exactly $1 back, ensuring that the cars behind me would be able to move more quickly.

I arrived at the Turning Stone Casino Resort shortly after 4:30 and secured my press credential an hour later from the lovely and talented Kelly Abdo. Once inside the arena, I began looking for my spot in the back of the second row, but less than a minute into my search I was beckoned by a security staffer who immediately recognized me.

“Your spot is up here,” he said. And what a spot it was – front row, two seats left of center. In other words, the equivalent of the 45-yard line at a game of American football. I spent the last 15 minutes before the undercard chatting with veteran scribe Robert Cassidy Jr., son of the onetime light heavyweight contender Bobby Cassidy. Not long after that, Beto Duran, the blow-by-blow man for tonight’s show being streamed on DAZN, walked up to my work station, extended his hand, and declared “it’s so great to finally meet you.” I felt like a star. I also chatted with ring announcer Joe Martinez, a man I dubbed “Mr. Smooth” for his pleasingly resonant delivery.

The seven-fight show began with a scheduled four-round super welterweight card between 18-year-old Floridian Sasha Tudor and 28-year-old Wyoming native Manuel Moreira. Tudor scored the first and only knockdown seconds after he connected with a thumping hook to the body, and, after Moreira arose, Tudor maneuvered him to the neutral corner pad, then unleashed an extended volley of power shots that prompted referee Charlie Fitch to intervene. The fight lasted just 70 seconds, and, with that, Tudor raised his record to 1-0-1 (1 KO) while Moreira’s declined to 1-6 (0).

Between fights, I spotted Hall of Famer J. Russell Peltz, whose fighter, 15-1 (5 KOs) welterweight Bryce Mills, was the “A-side” of the next contest, a scheduled six-rounder against journeyman Jose Marruffo, a Phoenix-based Mexican who entered the match with a 14-13-2 (2 KOs) record that included three losses in his last four bouts. Two of those three defeats came against undefeated prospect Cain Sandoval (KO by 6) last July and versus world title challenger Egidijus Kavaliauskas (KO by 3) last December.

Sporting trunks that bore the words “Don’t Blink” on the rear waist-band, the well-muscled Mills eagerly exchanged with the ultra-aggressive Marruffo, who successfully kept Mills on the back foot but was still absorbing the majority of the punishment.

The pattern continued in round two, and as I watched the fighters engage in toe-to-toe warfare, I couldn’t help but think that this was a Peltz special that would have been at home inside his old haunts of the Blue Horizon and the Spectrum.

At the tail end of round two, Cassidy leaned in and said, “He (Marruffo) is getting tired,” and in that instant, Mills broke out into a wide grin that indicated he knew it as well. If he was, he didn’t show it at the start of the third as he tore after Mills in whirlwind fashion. However, his rally didn’t last long enough to make a serious dent, and as the round proceeded, Mills’ quicker feet, faster blows and harder connects took over. The difference in stamina was made crystal-clear as Mills stood in his corner between every round while both of Marruffo’s arms consistently rested on the third-highest strand of ropes.

The decision was unanimous for Mills, and while two of the judges turned in 60-54 scorecards, the third saw fit to give one round for Marruffo. The A-sider did A-side things, but the B-sider made him earn his pay while also justifying his own check. In other words, this was a nice table-setter for Mills in the micro view and a learning experience for him in the macro view.

Next up was the opening contest of the DAZN broadcast, a scheduled six-round light heavyweight match between undefeated Mexico City native Yair Gallardo and 7-2 (5 KOs) Puerto Rican Michael Ruiz, fresh off a sixth-round TKO loss to Gian Garrido in March. The Mexico-Puerto Rico rivalry produced the expected split in the crowd reaction. As the fight began, I turned to Tris Dixon, who was seated two spots down from me, and said that the stoic, heavy-browed Gallardo looked like a right-handed Daniel Zaragoza with more hair and less scars, and he didn’t disagree. However, once Gallardo began punching, his blows produced a different sound, one like hollow thumps, than those delivered by Ruiz, and one punch to the side of the head prompted an involuntary “ooooh” from me. Ruiz’s face was noticeably red by the end of round one and I had the feeling the fight wouldn’t last much longer. I was right; the assault continued in the second, so much so that referee Benjy Esteves intervened at the 1:18 mark to a brief chorus of boos. Yes, he could have allowed the fight to continue, but what would have been the point? To me, Esteves acted properly, and a few of my ringside mates agreed.

Between bouts, Ring’s editor-in-chief, Doug Fischer, assumed his assigned spot to my immediate right, and, after chatting for a while, we settled in for the next fight of the evening, a scheduled eight-round super middleweight bout between the 13-1 (9 KOs) David Stevens of Reading, Pa., and the 14-5 (10) Sergio Lopez of Argentina. For Stevens, this was intended to be a “get-well bout” following his stunning first-round KO defeat to Joeshon James last October, and while Lopez was coming off a third-round TKO win over countryman Sergio Carabajal last December, he was in the midst of a 2-3 slide and was making his first appearance on U.S. soil.

Although the fight lasted just 133 seconds, the fans in the stands and some of the writers in press row were amazed. A whistling hook to the jaw scrambled Stevens’ senses, and it was all he could do to remain on his feet. He staved off disaster by twice tackling Lopez to the canvas, but the Argentine’s wild-swinging assault continued to spark very real visions of an impending upset.

Just when it appeared Lopez was ready to apply the finishing touches, Stevens suddenly lashed out with a two-punch combination that caused the South American to pitch forward on his face. Lopez somehow pulled himself upright, but another pulverizing hook-cross to the chin closed the curtain on this topsy-turvy firefight.

How fitting: Just two days before Argentina’s Luis Angel Firpo was to be inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame based, in part, on his legendary but losing effort against Jack Dempsey in 1923, his countryman Lopez ended up being on the losing end of an early-round shootout after having severely hurt the favorite and having him on the verge of a possible KO defeat.

The card resumed with the arrival of unbeaten junior welterweight Mykquan Williams, whose promoter is 2024 IBHOF inductee Jackie Kallen. His opposition was quick-twitch southpaw Willmank Brito, a 36-year-old Mexico-based Venezuelan who turned pro when Williams was 16 years old and who was fighting just 63 days after suffering a first-round TKO loss against John Bauza in Puerto Rico, his second KO defeat in his last four bouts. Moreover, this marked Brito’s debut on the U.S. mainland. As for Williams, this marked the second consecutive year in which he appeared at Turning Stone during IBHOF Induction Weekend. The first time, he fought another southpaw foe in Brazilian Paulo Galindo, and more than a few observers believed Williams was fortunate to exit the ring with an eight-round draw.

Here, Williams started well as he repeatedly struck Brito with lightning-quick but singular counterstrikes to the head and body, and though these opening connects produced concussive sounds, they lacked the power to seriously hurt Brito. That all changed when a right to the jaw wobbled Brito in round three, but seconds later, Williams suddenly found himself on the canvas. Following a moment of hesitation, referee Mark Nelson called the tumble a slip, igniting a chorus of boos from the underdog-friendly throng.

Up to this point, Williams and Brito appeared to be authoring a compelling story. Williams then slammed the book shut with a rifle-shot right to the jaw that sent Brito down, and ultimately out, as Nelson waved off the fight at the 2:57 mark.

With that, Williams exorcized the memories of last year’s disappointment and replaced it with a sizzle-reel quality KO.

The co-feature pitted welterweights Eric Tudor of Fort Lauderdale and the uniquely named Roddricus Livsey of Atlanta. Livsey, who, at 41, was 19 years Tudor’s senior, sported fabulously multi-colored trunks and orange-and-black shoes that would have found an appropriate home inside Smitty’s closet. To see said closet, check out Part I.

Within seconds, Tudor was blasting holes through Livsey’s high guard while also smoothly circling away from his opponent’s wild offerings. A crunching right to the ribs left Livsey crawling on all fours, and the pain from the blow kept him down for referee Charlie Fitch’s 10-count. The end came 139 seconds after the beginning, and given the brevity of the undercard bouts, one had to wonder how long we would have to wait before the main event fighters – WBO strawweight champion Oscar Collazo and challenger Gerardo Zapata – would be brought out.

The answer: 31 minutes.

The story lines surrounding this fight were intriguing. Since turning pro in February 2020, one can fairly say that Collazo has been surrounded by greatness. First, his mother named him Oscar because Oscar De La Hoya was her favorite boxer. Second, he is co-promoted not only by De La Hoya, but also by Miguel Cotto, both of whom are enshrined in the International Boxing Hall of Fame. Third, he won a widely recognized world title in his seventh professional fight, duplicating the accomplishment of Hall of Famer Jeff Fenech and of future enshrinees Vasiliy Lomachenko (who won his second divisional belt at this juncture) and Kazuto Ioka. Fourth, he has been mentored by 2024 IBHOF honoree Ivan Calderon. Fifth, he will be defending his WBO strawweight championship against Zapata, the 11th-ranked contender, just miles from the IBHOF museum. Finally, the audience for which he will be performing includes more than its share of boxing luminaries.

By fighting Zapata, Collazo will be competing against his second consecutive Nicaraguan opponent – he stopped Reyneris Gutierrez in three rounds in January – and should he win, his promoter indicated that he would welcome a title unification match against WBC counterpart Melvin Jerusalem, the man from whom Collazo won his WBO title in May 2023 (Jerusalem scored an upset split decision against Yudai Shigeoka in Japan on March 31 to win his current belt). If that fight doesn’t materialize, Collazo could face Ginjiro Shigeoka, the IBF champion and younger brother of Yudai. Then there is the elder statesman of the weight class, Thammanoon Niyomtrong (a.k.a. Knockout CP Freshmart), who has held the widely recognized version of the strawweight title since June 2016 but, as boxing’s current longest-reigning champion, has not defended it in nearly two years.

As for Zapata, he was scheduled to challenge WBO junior flyweight champion Jonathan Gonzalez last October 27 in his hometown in Managua after Gonzalez’s original opponent, Leyman Benavides, withdrew. But Gonzalez fell ill during fight week, and because there wasn’t sufficient time to find a suitable opponent for Zapata, the man nicknamed “Rattlesnake” was dropped from the show altogether. Since then, Zapata notched a 10-round draw against Azael Villar, so, when combined with the two-round disqualification loss to Rene Santiago, he had not won a fight since scoring an eight-round unanimous decision against Byron Castellon in January 2022.

Adding to Zapata’s degree of difficulty is that he will be fighting on U.S. soil for the first time and that his last eight wins have been by decision. In fact, his last KO victory took place in December 2018 when he stopped Jenn Gonzalez in round six, the final notch in his career-high five-fight KO streak. And, by the way, this will be Zapata’s first scheduled 12-rounder and he has fought past round eight only once – the 10-round draw against Villar.

However, based on his fights against Castellon and Villar, Zapata, a southpaw like Collazo, appeared to be a solid operator, and based on the video I saw, the Villar draw that was staged in his opponent’s home country of Panama had the scent of home cooking. With the rash of upsets lately (Usyk-Fury, Cacace-Cordina, Kabayel-Sanchez, Berinchyk-Navarrete), perhaps Zapata could add his name to this roll call.

The early stages graphically illustrated the gulf in speed and upper-body movement between the two. Collazo showed skill far beyond his limited number of professional fights, and he demonstrated a versatility with the right hand that is unusual for southpaws.

“He’s closing the distance faster than I expected,” Fischer said during round two, and he was right. At least until Zapata suddenly lowered the boom.

A wide-arcing counter right hook to Collazo’s jaw turned the champion’s legs to jelly, and it required all he had to keep himself from hitting the canvas. Zapata, potentially moments away from snatching the crown from Collazo’s head, went all out for the KO, and as he did, he plunged Collazo into the unfamiliar position of having to survive. But survive he did as he moved, clinched, held and ran out the clock.

“He caught me with a big shot, but we managed to box it out, box intelligently,” he’d say after the fight, positioned to my immediate left at ringside. “The game plan was set and we carried out the plan.”

Collazo appeared to successfully reassemble himself between rounds two and three, but as he drilled holes through Zapata’s guard, the element of danger emanating from Zapata’s fists appeared ever present. Happily, from Collazo’s standpoint, that element lessened with each passing minute, and by the fifth he appeared completely recovered. By doing so, Collazo was in the process of proving that his resiliency was a match for his well-honed physical skills.

By the final minute of the sixth, those skills enabled Collazo to force Zapata on the back foot, and by the eighth it appeared the challenger had shot his bolt as the speedier champion sliced, diced and dissected.

Collazo punished Zapata down the stretch of their strawweight bout. (Photo by Cris Esqueda / Golden Boy)

“I knew I was in control by the fifth or sixth round,” he said. “He was looking for one shot; he caught me with that one shot, but I didn’t let him hit me again.”

I told multiple people that I thought Collazo would score the TKO between rounds seven and nine, but instead the bout completed the scheduled 12-round distance, and, like his mentor Calderon, Collazo used his southpaw wits and hits to seize firm control of the proceedings.

As the clock ticked down toward the final minute, Collazo paid brief tribute to the “Iron Boy” with a duck-under move that caused a small part of the crowd to shout “ole!” as past throngs had done so many times for Calderon.

“I heard it, and it felt good,” Collazo said.

In the end, Collazo produced the kind of lopsided scorelines that were a regular part of the 2024 IBHOF inductee’s resume – 119-109 twice and 117-110.

When asked if this was the biggest victory of his career, given the adversity he confronted, he replied, “It’s not the biggest victory of my career, but it was the hardest. I wasn’t entirely happy with the performance. If I see it again, I might like it, but I also want to see what mistakes I made and correct them.”

In retaining his world title for the third time, the man named “El Pupilo” (“The Student”) was Zapata’s teacher. He said he hoped to teach his next course “in September or October. I want it to be in Puerto Rico, but let’s see what happens.”

After cleaning up my copy, I unplugged the laptop, said goodbye to Dougie and headed for my car. After stopping to get a late-night snack, I perused my copy, settled down and called it a day.

*

Lee Groves is a boxing writer and historian based in Friendly, West Virginia. He is a full member of the BWAA, from which he has won 22 writing awards, including two first-place awards, since 2006. He has been an elector for the International Boxing Hall of Fame since 2001 and is also a writer, researcher and punch-counter for CompuBox, Inc. as well as a panelist on “In This Corner: The Podcast” on YouTube. He is the author of “Tales from the Vault: A Celebration of 100 Boxing Closet Classics” (available on Amazon) and the co-author of “Muhammad Ali: By the Numbers” (also available on Amazon) as well as the 2022 winner of the BWAA’s Marvin Kohn “Good Guy Award.” To contact Groves, use the email [email protected] or send him a message via Facebook and Twitter (@leegrovesboxing).